Ag. History Through Soil Carbon Chemistry

Wendy Munson-Scullin, March 2023

This is a research project I’m developing as an offshoot working with soil carbon chemistry in Archaeology. This is my original work, its publication here is not permission to reproduce text or images (ask me), and is not advice. My contact information can be found in the tabs along the top of the page.

There are interesting (and explicable) anomalies in soil carbon chemistry in tilled agricultural systems compared to never-tilled soils that do not show up in standard soil carbon tests, such as organic matter, or total carbon. Those anomalies tell us about history and stability of the soil system overall. In other words – addressing the question, “What is the state of, or the quality of the carbon compounds?” Rather than, “What is the quantity of carbon that can be measured?”

“Quality vs. quantity” of soil carbon compounds isn’t a distinction without a difference. It’s the history of a soil profile. And it’s an indicator of the functionality the soil-plant system.

“Soil carbon quality” isn’t about a single component. It refers back to the entire community involved in depositing (sequestering) that carbon in the soil.

Plowing or tillage injects the soil with air and exposes the buried parts to sunlight. Result: Breaking open carbon compounds in the soil. That’s why it works. That disturbance and its effects on soil carbon are still detectable decades later. (Soil nerd, applying an archaeology/soil-history mindset, right here). Evidence of that is below.

Research questions:

- What practices can reverse that trend – to increase carbon complexity to become more like never-tilled soils?

- What sort of time-frame is reasonable to achieve that goal?

- Are those practices economically and practically sustainable in the near-term? Long term?

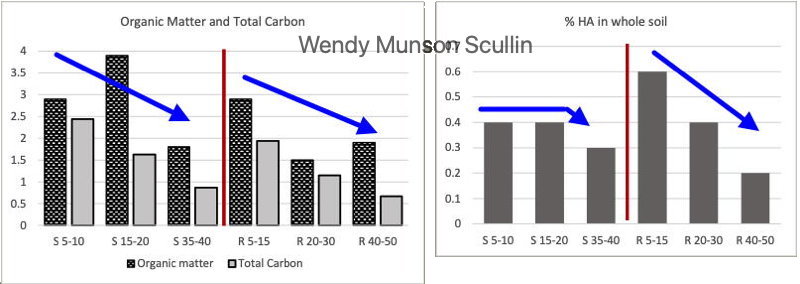

Below are the organic matter and total carbon results from two soils of similar soil-type, taken at 3 different depths (indicated in centimeters). The difference is that one has never been tilled and the other was a hayfield and pasture, any other cropping is unknown, but possible. The hayfield/pasture has been un-used in over 2 decades.

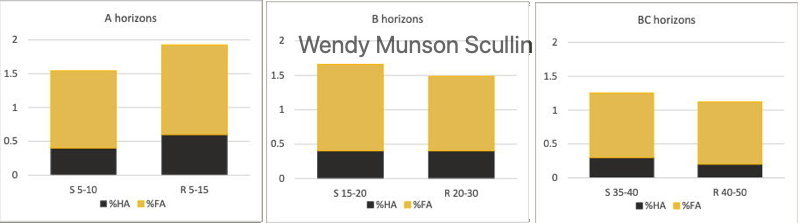

Below is a result from two soil carbon extraction processes I use (also featured in the above-right chart). These represent a chemical spectrum of soil carbon compounds which can be categorized as humic acids and fulvic acids. Humic acids includes carbon which is not readily water-soluble, which is likely to be stable in an undisturbed soil, and much of which likely has been transformed from its original state by soil organisms (soil biology). Fulvic acids are organic matter which may have been transformed (more and/or less) by soil organisms, as well as exudates from soil biology (roots, microbes, fungi, invertebrates). The difference is that fulvic acids are soluble in water at neutral or acidic pH whereas humic acids are not. Both humic and fulvic acids are beneficial for plants and also for soil-living organisms, both are highly active components of soil communities for plants and for soil microbes.

Compared to the Organic matter and Total carbon, the A horizon is lower in humic acids where it was tilled, hayed and pastured. And despite having been in grass cover for decades, that cover was almost completely cool-season grasses (brome, bluegrass, some timothy). That means there was not ideal underground diversity – so even with a grassy cover – this was a system that was not recovering as well as it might have, were it more intensively managed with a goal of soil-health. Or I might say – with a goal of recreating in the tilled system as many of the functions as are present in that never-tilled system. This is something I hope to pursue with a larger number of samples. I was reproducing results obtained by European researchers in the Canary Islands, after spending all winter working the bugs out of the protocols to make them Iowa-Soil-Friendly. The difference between the organic matter and total carbon results (processed at an outside lab) is pretty intriguing!